Yesterday evening, one of my students with a notable disability of some kind (either physical or mental or emotional, I can't be certain myself) interrupted the mundane conversation the school's math teacher and I were having about the usual teacher nonsense (when the meeting or grades or something was going on... maybe we were talking about exams? I don't remember) to tell the math teacher all about how King Xerxes invaded Greece with an army of 2 million men thus sparking the Second Persian War.

I about collapsed.

The math teacher sat there beaming, listening to this student recount the story of three centuries of Greek and Persian history with one of the most excited tones. He repeated me verbatim, acting out the wild battle I had vividly described to his class earlier in the day.

But he didn't stop there. He just had to tell his math teacher (and because I was standing there, I suppose me, too) all about everything he had learned in history for about the last two weeks of school. I knew the kid was smart, but he's always had trouble communicating with me and with others in anything resembling an organized fashion. A month ago, I told him that I was advancing him to the "next level in the video game that is history class". I told him that before he speaks, he should write down what he intends to say and then read that. He was skeptical, yes, but everytime the lad speaks in class now, he gets applause from his classmates. I tried to discourage this, but it was genuine and spontaneous and I stopped when I saw how positive an experience it was for him. Once organized, he is perhaps one of my smartest and most articulate students. And he works hard.

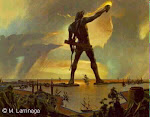

And he wowed me again and made me feel that I had accomplished something. Here is a student that others have written off as "slow" and "awkward" and a pain. He reminds me in MANY ways of Steve Urkel, but in the loveable way (I think I've heard him say "Did I do that?" once or twice). He is in some ways all of these things, and yet he learned the Persian Wars. And he learned the important history leading up to it, including Athenian help for the Ionian Revolt. He personally reenacted the Battle of Thermopylae, which he told the math teacher is Greek for Hot Gates. I had tears in my eyes listening to it all.

When the boy scampered off down the hall to get home, the math teacher and I stood alone in the hallway staring after him in silence for what felt like 30 seconds or a minute. We turned to each other and he patted my shoulder with his gloved hand and said, "Well, you got through to someone." I nodded my stern nod that I've developed, smiled, said good night and walked back into my classroom. The Math teacher turned to leave and said the same.

Christmas break is here and for all of us - students, teachers, staff - it could not have come at a better time. We're drained. I feel like I've emptied myself of every last ounce of strength I have for these kids. I've exhausted myself in planning and in grading and in praying and in disciplining and in just being a teacher for practically every single waking moment of every single day. I have to stop myself from telling strangers on the subway in New York to spit their gum out on weekends when I'm in the city.

I teach history. And I'm beginning to wonder if I've not been making it all along for and with my students. A girl in my homeroom told me today that the greatest history of all is the kind "you" make. I presumed she meant "you" in the sense that the grammatically-correct mean "one", but she corrected me and said, "No, Mr. Cochran, the history you [pointing to me] make." And then she hugged me and left. I was stunned. And many of the other kids said less poignant though equally telling things (not to mention all the Christmas gifts they gave me over my loud objections).

I teach history. My students teach me that being human means more than just being good. It means growing, even when it seems impossible to grow. The moments like the ones described don't happen to me everyday. I suppose I'd write every day if they did. But they happen often enough to remind me that I'm on the frontline of history everyday.

How fortunate am I to be present at such awe inspiring moments as these. How fortunate am I to teach & make history.

Friday, December 21, 2007

Monday, December 17, 2007

Stille Nacht

There was an incident on Thursday last that unfortunately I cannot publish here, but suffice it to say, I made a mistake. The fallout from that day lingered for roughly 24 hours - though I expected it to have lasting implications. I learned from it, my students learned from it, and we've all been able to move on.

But something I've noticed about mistakes before now is that making them some how brings people closer together. It's almost as if they affirm our humanity, they teach us both about the specific instance at issue, but they also teach us more broadly about what it means to be human. Teaching is, in many ways, the science of being human. Teaching itself is an art, but the matters confronted by teachers are for civilized society radically a part of the very fabric of life. To read, to write, to think, to debate, to decide, to conform, to stand out, to cipher, to approach problems logically, to be something distinct while being a part of something larger... education accomplishes these things for young and old alike. When students are told a teacher is a human being and can make mistakes, it is as some fact in some dusty book, detached from reality, other & separate from the here and now.

But when students witness a teacher make a mistake, well... the fact becomes more real. Just as it is far easier to teach students about the Peloponnesian War by having the two (or more) sides of the classroom take sides in the conflict even as it is lectured to them, it is also far easier for students to grasp the humanity of a teacher should they witness that humanity played out in that most "unlikely" of ways, namely, the mistake.

Friday came following Thursday as a million other Fridays have followed a million other Thursdays since time immemorial (though we skipped a week and some in 1582 when Thursday October 4 was followed by Friday October 15). Despite my past observations, this Friday flowed smoother. Students that had never bothered to pay attention suddenly felt compelled to, students that had treated me with indifference showed a new found respect... rule by fear is hardly what I desire or require, but I won't say with certainty that it was fear that drove the new order that has persisted through the momentum destroying weekend into today.

Students have begun to try for me, to push themselves. Certainly I still have the few that are not college prep material, but there again, I have others that I had discounted until only recently. The preparation for Christmas continues in all of my classes as I struggle to bring students forward in time into the Hellenistic Age and the rise of Rome. But with only minor problems, blips as they were, I am making genuine progress that would be written off by any other institution but which I must grab onto for the sake of my own sanity, progress that even I should have called impossible only two months ago. Indeed, my own writing on this blog back in its infancy might well have expressed skepticism at the life I've seen in a few of my more precarious wards.

With Christmas only a week away and as time continues to slide forward, I pause and reflect at the night that reigns. But even as I do, I cannot help but picture the three burning candles of the Advent wreath that my religion class and I gathered around this morning. We sang "Adeste Fideles" in the original Latin (the little troopers gave their best shots) and "O Come O Come Emmanuel" and then we sang one of their favorites, "Silent Night," but I printed up lyrics for several of the stanzas and I added in a Spanish stanza for my Hispanic students and for the others to practice. And then I finished with the original verse that had been written in German.

They stood and listened with wide-eyed awe at the sound of the other language as it came from my mouth. I'm not the best singer in the world, but years of choir (including one Christmas when I sang "Stille Nacht") put me in a position to bring the carol to them in a meaningful way.

I was able to get students in a Newark High School to listen to me sing "Silent Night" in German, to appreciate it, to admire it, to ask me to sing it again... I don't know how many times I will experience moments like this in my life.

However many times it is, for now, I'm just going to sit back, grade papers, and enjoy the quiet of the Stille Nacht.

But something I've noticed about mistakes before now is that making them some how brings people closer together. It's almost as if they affirm our humanity, they teach us both about the specific instance at issue, but they also teach us more broadly about what it means to be human. Teaching is, in many ways, the science of being human. Teaching itself is an art, but the matters confronted by teachers are for civilized society radically a part of the very fabric of life. To read, to write, to think, to debate, to decide, to conform, to stand out, to cipher, to approach problems logically, to be something distinct while being a part of something larger... education accomplishes these things for young and old alike. When students are told a teacher is a human being and can make mistakes, it is as some fact in some dusty book, detached from reality, other & separate from the here and now.

But when students witness a teacher make a mistake, well... the fact becomes more real. Just as it is far easier to teach students about the Peloponnesian War by having the two (or more) sides of the classroom take sides in the conflict even as it is lectured to them, it is also far easier for students to grasp the humanity of a teacher should they witness that humanity played out in that most "unlikely" of ways, namely, the mistake.

Friday came following Thursday as a million other Fridays have followed a million other Thursdays since time immemorial (though we skipped a week and some in 1582 when Thursday October 4 was followed by Friday October 15). Despite my past observations, this Friday flowed smoother. Students that had never bothered to pay attention suddenly felt compelled to, students that had treated me with indifference showed a new found respect... rule by fear is hardly what I desire or require, but I won't say with certainty that it was fear that drove the new order that has persisted through the momentum destroying weekend into today.

Students have begun to try for me, to push themselves. Certainly I still have the few that are not college prep material, but there again, I have others that I had discounted until only recently. The preparation for Christmas continues in all of my classes as I struggle to bring students forward in time into the Hellenistic Age and the rise of Rome. But with only minor problems, blips as they were, I am making genuine progress that would be written off by any other institution but which I must grab onto for the sake of my own sanity, progress that even I should have called impossible only two months ago. Indeed, my own writing on this blog back in its infancy might well have expressed skepticism at the life I've seen in a few of my more precarious wards.

With Christmas only a week away and as time continues to slide forward, I pause and reflect at the night that reigns. But even as I do, I cannot help but picture the three burning candles of the Advent wreath that my religion class and I gathered around this morning. We sang "Adeste Fideles" in the original Latin (the little troopers gave their best shots) and "O Come O Come Emmanuel" and then we sang one of their favorites, "Silent Night," but I printed up lyrics for several of the stanzas and I added in a Spanish stanza for my Hispanic students and for the others to practice. And then I finished with the original verse that had been written in German.

They stood and listened with wide-eyed awe at the sound of the other language as it came from my mouth. I'm not the best singer in the world, but years of choir (including one Christmas when I sang "Stille Nacht") put me in a position to bring the carol to them in a meaningful way.

I was able to get students in a Newark High School to listen to me sing "Silent Night" in German, to appreciate it, to admire it, to ask me to sing it again... I don't know how many times I will experience moments like this in my life.

However many times it is, for now, I'm just going to sit back, grade papers, and enjoy the quiet of the Stille Nacht.

Monday, December 10, 2007

What I've learned in the interim

Sorry to all my loyal readers who've felt left out of my teaching experiences without my frequent reflections. I should be able to get back on some semblance of a normal routine now that progress reports are done and my planning and grading are caught up.

Since last writing, I've learned a few practical things: first, don't collect 120 journals all at once and then expect to read them all thoroughly in a brief amount of time; second, it is vain of a teacher to believe they've taught their students something after only once teaching it, especially when that something falls under the category of "modern political discussion material." Even if the issue under discussion is misunderstood in wider society and that is why it is discussed anyway, do not presume to think you can clear away the fog and lead people to understanding just like that. If people are already believing the world was created in 7 days, then simply telling them that Genesis is not a scientific description of the creation of the universe is not going to end the problem.

I've learned it's very easy to feel like a failure even when you're not. It's also easy to come out of that feeling so long as you have people around you who see the same thing you see and tell you that you're not a failure. Teaching is very much an art. Not that I think I'm a master, but even the great masters of painting and sculpture reviled some of their own greatest masterpieces even as the rest of humanity basked in their beauty. I've reflected before on the need to focus more on the big picture, but it is so hard to live beyond the immediate moment when the student will not behave, will not follow directions, will not be serious about a given situation, just wills not to comply. It is so hard.

I've also had the experience of dealing with the old cliche, "You can lead a horse to water, but you cannot make him drink." Last week, as I sat to prepare progress reports, I found myself facing the fact that one of the students in my home room had not handed in either a history journal (participation grade) or his religion journal (project grade). I sat him down after school and just put all the cards on the table and told him, "Look. You're failing almost beyond recovery for not handing in your work. The time to hand these things in has more than elapsed, but I'm going to break my own rule and let you take until this coming Monday [today, 12/10; the conversation happened on 12/5] to get these things done." He cried and thanked me for giving him the extra time. I saw a genuine desire to do better.

He didn't have his journals today. He "had a game to go to this weekend."

I put the zeros in my grade book right in front of him and let him watch his average change. He cried again, but this time I had no pity. I asked him, point blank, if he cared. His response was, "Of course I care!" and my response, flatly, was, "It certainly doesn't look like it, does it?" pointing to his averages.

When I was in high school, I was public enemy number one when it came to not handing in math homework. I would start out the semester doing it, but way would lead onto way and I'd get caught up in my other classes and I'd try to do my math homework but it would take me too long and I would rarely understand all of it until we had moved on to the next section - by which time it would be too late to do the old homework anyway since I now had new homework to do. So I just didn't do it.

I tried to put this student into that same mold, but in this student's case my class isn't math, it's history and religion. And the assignment isn't problems 1-49 every-other-odd, it's write a page worth of reflection on a given prompt that he is given time in class to write on (not to mention a great deal of time at home). The excuses I gave in my discussion of math homework were not sufficient then and are not now, but they explain why I didn't do it. For this student, I'm left with the conclusion that either he cannot do the work - and his general writing ability that I've seen does not reflect this - or he will not do the work. He "has a game to go to."

I told the student that, one way or another, he would learn from me before he left my class: either he would master my class's curriculum, or he would learn a very important life lesson. I didn't tell him that I had to learn a comparable life lesson in high school myself. I'm really hoping I don't have to teach him a lesson about failure, but then again, I suppose it's better he fail me now on a report card than he fail a job later and lose his house.

And that's what I've learned in the interim.

Since last writing, I've learned a few practical things: first, don't collect 120 journals all at once and then expect to read them all thoroughly in a brief amount of time; second, it is vain of a teacher to believe they've taught their students something after only once teaching it, especially when that something falls under the category of "modern political discussion material." Even if the issue under discussion is misunderstood in wider society and that is why it is discussed anyway, do not presume to think you can clear away the fog and lead people to understanding just like that. If people are already believing the world was created in 7 days, then simply telling them that Genesis is not a scientific description of the creation of the universe is not going to end the problem.

I've learned it's very easy to feel like a failure even when you're not. It's also easy to come out of that feeling so long as you have people around you who see the same thing you see and tell you that you're not a failure. Teaching is very much an art. Not that I think I'm a master, but even the great masters of painting and sculpture reviled some of their own greatest masterpieces even as the rest of humanity basked in their beauty. I've reflected before on the need to focus more on the big picture, but it is so hard to live beyond the immediate moment when the student will not behave, will not follow directions, will not be serious about a given situation, just wills not to comply. It is so hard.

I've also had the experience of dealing with the old cliche, "You can lead a horse to water, but you cannot make him drink." Last week, as I sat to prepare progress reports, I found myself facing the fact that one of the students in my home room had not handed in either a history journal (participation grade) or his religion journal (project grade). I sat him down after school and just put all the cards on the table and told him, "Look. You're failing almost beyond recovery for not handing in your work. The time to hand these things in has more than elapsed, but I'm going to break my own rule and let you take until this coming Monday [today, 12/10; the conversation happened on 12/5] to get these things done." He cried and thanked me for giving him the extra time. I saw a genuine desire to do better.

He didn't have his journals today. He "had a game to go to this weekend."

I put the zeros in my grade book right in front of him and let him watch his average change. He cried again, but this time I had no pity. I asked him, point blank, if he cared. His response was, "Of course I care!" and my response, flatly, was, "It certainly doesn't look like it, does it?" pointing to his averages.

When I was in high school, I was public enemy number one when it came to not handing in math homework. I would start out the semester doing it, but way would lead onto way and I'd get caught up in my other classes and I'd try to do my math homework but it would take me too long and I would rarely understand all of it until we had moved on to the next section - by which time it would be too late to do the old homework anyway since I now had new homework to do. So I just didn't do it.

I tried to put this student into that same mold, but in this student's case my class isn't math, it's history and religion. And the assignment isn't problems 1-49 every-other-odd, it's write a page worth of reflection on a given prompt that he is given time in class to write on (not to mention a great deal of time at home). The excuses I gave in my discussion of math homework were not sufficient then and are not now, but they explain why I didn't do it. For this student, I'm left with the conclusion that either he cannot do the work - and his general writing ability that I've seen does not reflect this - or he will not do the work. He "has a game to go to."

I told the student that, one way or another, he would learn from me before he left my class: either he would master my class's curriculum, or he would learn a very important life lesson. I didn't tell him that I had to learn a comparable life lesson in high school myself. I'm really hoping I don't have to teach him a lesson about failure, but then again, I suppose it's better he fail me now on a report card than he fail a job later and lose his house.

Since last post, I've aged a year further and I've come to realize that adults aren't really that much smarter than kids. I know adults that are much less intelligent than some of my students. The difference is in the experiences, the mistakes, the lessons learned. The great tragedy is that with all the brainpower that humans have, we're rarely smart enough to learn from the mistakes of others, especially from others who have authority over us. For someone like me, teaching is as much a Purgatory as it is a Paradise; every time I get on a student for not handing in work, I feel my inner voice getting on me for the same reason. I have no idea what to do about that, assuming it's even something that needs attention.

And that's what I've learned in the interim.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)